As well as being occasionally witty and often cute about the life and work of philosophers, this series of comic-book-type intros does a surprisingly good job of getting across the central ideas of just about everyone from Plato to Derrida. I like it.

1

1

Artists without Sales

A decade-by-decade history of the Group of Seven's exhibitions, etc., There are lots of images of the paintings, and especially interesting, lots of images of pictures by less-often reproduced members of the group and also, by their various associates and/or enemies; so there's more of a context for the well-known paintings by Jackson, Harris, and such. (The book accompanies an exhibit held at the National Gallery of Canada, which has a particularly rich collection of Canadian painting of the first half of the twentieth century.) Charles Hills' text offer a knowledgeable view of the Group in the context of the Canadian art milieu of their time, so there's lots about criticism of their work by those who preferred more traditional styles, about the political machinations of the boards of galleries, and so on. Hill particularly focuses on sales as an indicator of reputation--and usually has to make the bleak point that hardly any sales resulted from the Group's exhibits throughout the twenties.

One of the painters whose work Hill includes is Prudence Heward, who exhibited in the Group of Seven shows in the late twenties and early thirties. This is Heward's charming but honest At the Theatre.

So Many, Many Moments--and Not Enough Definition

The main text of this history of inuit art follows developments decade by decade and community by community--a process of list-making that seems to be accurate but is rarely all that interesting. i'd been hoping for more about what it is that distinguishes this art generally and what is interesting about various individual pieces. And I'd like to know more than the little provided here about how Inuit art relates to developments elsewhere, and how trends elsewhere were the context for its successful reception over the decades. Still, there are excellent photographs of a lot of fascinating pieces here, so it's a book well worth looking at. I just wish it had more to say about what the work is and what it does.

The book, by the way accompanies the 2013 show at the Winnipeg Art Gallery of pieces from its vast collection of inuit art, also called Creation and Transformation. Looking at that show, I had a particularly strong response to a serigraph by Stanley Elongnak Klengenberg called Cold and Hungry.

The Group of Seven in International Contexts

The Group of Seven painters--especially Harris and Jackson--were avid proselytizers of their own work, and they and some of their fans developed a set of ideas about its significance that soon turned into a set of still widespread misconceptions about it. Their insistence on the distinct Canadian-ness they aspired to, and the importance of distinct northern Canadian landscapes in their efforts to achieve that distinctness, turned into a general misperception that they were the first artists to paint the Canadian wilds and that their vision of it emerged from a direct contact with those wilds, unhampered by much knowledge of European traditions of painting. That they themselves made so much of their friend Tom Thomson's lack of formal artistic training and his presumed status as a knowledgeable and virile woodsman also contributed to the idea that these artists were inspired almost purely by the spirit of the places they painted--places that represented the true and distinct soul of what it means to be Canadian in ways that were more manly than the prissily over-civilized work of other Canadian artists who were steeped in the traditions of European academies.

In Defiant Spirits, Ross King does a really good job of deflating these peculiar myths. He carefully explore the various art schools the members of the Group attended, many of them in Europe, and finds in their correspondence and elsewhere a large and very specific knowledge of what were then current trends at the cutting edge of art across Europe. He shows how very much the Group's paintings display a knowledge of post-Impressionist artists like Van Gogh and Matisse, and reveals intimate connections between individual paintings by the Group and their specific models and influences. He also discusses a fairly long history of earlier and other artists who painted the landscapes of the Canadian shield, albeit in different styles. In demythologizing the Group, King shows exactly how knowledgable they were, and how dextrously they used their knowledge to create something that was indeed distinctly Canadian--a specifically Canadian and richly meaningful response to what they knew was happening in art internationally.

This is an important book, I think, and one that makes me realize that artists like Thomson, Harris, Jackson, and MacDonald are more important, more interesting, and to be taken more seriously, than I had previously imagined.

A Book App

I actually have not read this on paper--what I looked at was the book app, which includes moveable photos, music playlists, videos of performances by Liberace and others, and so on. It ends up offering a very choppy story experience--after listening to eight or nine tracks of music, it's hard to remember which of the characters was inviting you to check the tracks out or to think about why they might have any relevance to the events of the plot. The story seems to be about a romance between a piano prodigy with a demanding father and mental health problems and the nice artistic boy who moves in next door. But there's enough confusion in visual details and such that it's possible to entertain the idea that actually there is just one character here--either the girl imagining the boy or the boy imagining the girl, or someone utterly unknown imagining the both of them. See a commentary about these possibilities here:

This is a seriously annoying book, filled to the brim and beyond with unwarranted assumptions about Lawren Harris's motives and conscious and unconscious psychological quirks, most of which are based on little or no evidence at all. Harris himself was a fascinating person, a patrician inheritor of a sizeable fortune who decided to devote his life to creating art. And he produced many powerful pictures, especially of northern landscapes. But while this book does offer what I was hoping for--a sense of who Harris was and what happened to him in his life and especially, what part he played in the establishment of the Group of Seven and a distinctive Canadian art more generally, King is far too confident about his far-too-pop-psychological interpretations of Harris and his work for the book to be anything but infuriating. I was especially annoyed by this description of Harris's portrait of the woman who became his second wife: "The face is that of a person deeply attracted to and obviously in tune with theosophist principles; as such, it can be read as a tribute by the artist to his own religious beliefs. Yeah, sure. I wager that the vast majority of people selected randomly on the street and shown this painting would not immediately jump to the "obvious" conclusion that it revealed theosophical interests.  "

"

Oh yes, Roy McGregor, indeed you are. Northern Light is an intricately detailed and amazing complicated expression of speculation, wild guessing, and theorizing that in the long run reveals far less about the life of Tom Thomson than it thinks it does. And has surprisingly little to say about his work.

Surprising neat and symmetrical for a Dickens novel: almost every character is involved significantly in a child/parent relationship, and most of the plot lines deal with ways in which fathers and others can be good or bad parents and bless or blight their children's lives. There are parallel women ruined by their mother's greedy upbringing of them to use their attractiveness for profit--one fairly well off, the other very poor. There are opposing parents who either give their children no love (Dombey) or offer them a lot of it (the men who bring up Walter). There is a large family brought up lovingly and another large family beaten and boisterous. And there are various uncles and aunts in the role of parents. There's also a pretty intense sermon about how far from criminals acting "unnaturally," it's social conditions that blight the poor and produce crime. For a long time, almost nothing happens--but then there's a big payoff for that, as people frozen in their prideful relationships and others separated trough the machinations of their enemies all suddenly collide and explode in melodramatic soap opera.

Carl Barks's stories about Unca Scrooge and Unca Donald and the Junior Woodchucks are almost as much fun as I remember them being when I first read them sixty years ago--only now I think it'd be fascinating to try to work out the relationship between the depiction of Unca Scrooge's moneybin and the vast Disney moneymaking empire. Like, how did these Disney characters get away with satirizing all the values the Disney empire stands for? What is it about the satire that renders it harmless enough that the Disney empire happily allowed it?

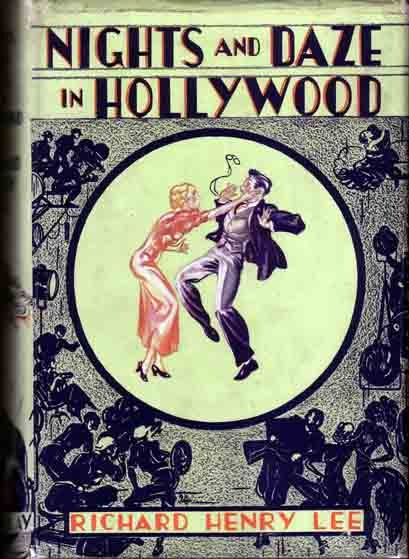

Nights and Daze in Hollywood, with the Emphasis on Daze

Satisfying junk. The would-be movie star Fanma Browo (nee Fanny Dopass) leaves New Jersey for Hollywood after her aunt leaves her a fortune of $50, 000--and this is in 1933, when a dollar was a dollar. She tells of her experiences with a vast array of conmen after her dough, in spirited letters to a friend back home, filled with bad spelling and even worse unintended puns about touching fannies and the like. Fanny is so completely dumb that she happily lets herself be taken for various rides, despite the attempts of her friend back in New Jersey to warn her about how she's being taken. But in the end, her old boyfriend Slim from back home, who has followed her west and suddenly, magically, become a very powerful movie director, saves the day and marries her. It seems nowhere near as scandalous now as it did when I was ten and sneaking peaks at the copy in my parents' bookcase. I wonder if either of them ever read it--I used to suspect that they just went to a used book store and bought enough books to fill the shelves once they had the bookcase, to make the place look tonier, because I never actually saw them reading all that much beside the newspaper and Reader's Digest Condensed Books. And I suspect my grownup mom would have found Fanma's suggestive puns even more scandalous than I did when I was ten. Luckily, she never caught me reading the parts of it that made me blush.

This is a novel I remember being in my parents's bookcase when I was young. It intrigued me because so many of the words were misspelled, but I remember that after starting to read it I stopped reading very quickly, because it seemed embarrassingly racy and wildly sophisticated. I found a copy online and bought it after the heroine's name popped into my head for no reason a few weeks ago: Fanma Browo. That turns out to be her stage name, though. Her real original name is Fanny Dopass. Like, how racy and sophisticated can you get? I suspect I'll have more to say when I've finished it, if I don't die of embarrassment first.

Why Isn't It Boring?

This is a book about boredom--mind-numbing, gut-aching, apparently eternal boredom. It goes on for pages and pages of ever-so-detailed descriptions of boring people being bored in the most boring of ways. And yet, magically, it was not ever for me the least bit boring. What I can't figure out is how Wallace managed to make such authentic-feeling descriptions of sheer boredom so totally fascinating. Wallace didn't finish this book himself before he died, and maybe he would eventually have found a way of making the writing as sutiably boring as its characters and its non-events. But as it is, it brilliantly defies its subject be being almost always so very interesting about it.