It has taken me a long time to read this book. The problem was not that I found it boring or difficult to read or unpersuasive—anything but. The problem was simply that it was too persuasive, and what it persuaded me of was profoundly depressing. I found myself resisting picking it up yet once more and going on to read yet more of, and be yet again convinced and depressed by, Kendi’s detailed and ugly history of the ongoing power of racist ideas in the United States (and really, for that matter, in Canada and Europe and elsewhere).

Kendi’s main argument is that, contrary to popular belief, the development of racist theories about human differences has not led to the racist behaviour that has marginalized, impoverished, and enslaved people of African origins in the US. Instead, the desire to use people as slaves, or to prevent them from having a political voice or a right to fair housing, or to otherwise take advantage of them and make money from doing so has preceded the development of the theories that justify that behaviour—and continues to do so.

There were people who wanted to buy and sell slaves before there was a theoretical justification for doing so. More recently, an urge to make money from the incarceration of massive numbers of Americans of colour has encouraged the development of theories of differences in racal intelligence and the misleading and inaccurate intelligence tests that still maintain them. they have also supported an unthinking faith in ideas of individual self-reliance, the dangers of welfare, etc. that still blames people of colour rather than economic conditions for their poverty. Those theories then allow for and sustain the ongoing existence of the slums and other social conditions that encourage poverty and lack of opportunity and thus lead to crime and profitable incarceration—and those in turn appear to confirm the racist theories that allowed the inequitable social conditions n the first place. Racist theory works by offering to account for why Whites have no choice but to take advantage of Black people, always by placing the blame on a theoretically-established and clearly false conception of Black inadequacy.

Kendi identifies three main types of racist theories. First is the idea that people whose ancestors came from different continents are inherently and unalterably different from each other and that Africans and Asians, etc., are inherently inferior to the Europeans who wish to take economic advantage of the supposedly inferior others, thus justifying taking that advantage. Second is the idea that matters like primitive social conditions or the hot African climate or later, the experience of slavery, have made people of certain races debilitated or without morals or otherwise inferior to the supposedly advanced Europeans, and so those other people need to be encouraged and helped to become more like Europeans before they can be treated equally. The third idea is antiracism, or the belief that all people are already and have always been equal to one in any way that matters, and it is those who think otherwise who need to change their ideas and also, change the laws and social customs, etc., that still now create differences and promote inequality, sometimes even by professing to combat it.

For Kendi, the beliefs of a lot of Americans of both African and European backgrounds who have played significant parts in the fight against slavery and other form of inequality, in the past and now, fall into the first two categories. There have been Blacks as well as Whites who have believed so fervently in the undeniability of racial difference that they worked for the development of a society of separate but equal races—forms of apartheid. And there have been both Blacks and Whites who have bought into the idea that Blacks have been made different and inferior by a history of ill treatment, and need to become better, i.e., almost always, more like Whites, in order to deserve, and before they can achieve, equality. These assimilationist views fall within Kendi’s second category.

For Kendi himself, only anti-racism is an acceptably safe position—the one that doesn’t sustain racism even while trying to fight it. He finds very few people throughout history or even now who represent it. That’s what makes the book so depressing—that, and the overwhelming evidence he presents to support the conclusion that the white suprematist ideas that have received so much attention in recent times are neither new or newly powerful. They have always been there, and they have always had more profoundly powerful effects on the lives of people of colour in North America than have public avowals of belief in or the passing of laws in support of equal treatment for all.

Stamped from the Beginning is well worth reading, in spite or, no, exactly because of, how depressingly convincing it is.

Maud and Everett and Everything Else

This gigantic book (492 pages about a woman whose life was, apart from a few major exceptions, uneventful) is a candidate for being one of the strangest pieces of writing I’ve ever encountered. The title promises a biography of the Nova Scotia folk artist Maud Lewis, and indeed, there’s a lot about her here, as much as anyone actually knows about her (and more that Woolaver has invented; but more about that later). But Maud is not by any means the only subject. Woolaver spends many chapters discussing not only the Poor Farm located next door to the little house Maud shared with her husband Everett, but also, the history of Poor Farms in Nova Scotia and elsewhere. He quite rightly justifies the significance of the Poor Farm in Everett’s childhood—he was kept there along with his entire family — and later also in Everett’s years with Maud—he was its night watchman for a long time; and he also points out that Maud, in the absence of indoor plumbing at home, often visited there to take baths and have her hair done. But Woolaver speaks often of his long-standing ambition to produce a book that would widen knowledge of the shameful Poor Farm system, and apparently thwarted by widespread lack of interest by publishers, etc., in revisiting this sad history, he has, in effect snuck the book about the Poor Farms into this one claiming to be about Maud. There’s a point where what feels like a hundred pages in a row about the Poor Farms lose sight of Maud altogether.

Nor is that the only way in which Woolaver interrupts his biography of Maud with lengthy discussions of other barely relevant matters—quite often, matters concerning himself. Attentive readers can learn at least as much about the forebears, family connections, education, work, publication and travel history, artistic and literary tastes, intense dislike of all current and past administrators of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, friendships and falling-outs, relatives, physical and mental illnesses, financial crises, bookshelf contents, filing habits, and character strengths and failings of Lance Woolaver as they can about Maud and Everett Lewis. This is endearingly wacky, but also, quite annoying.

Even when Woolaver does get around to talking about the Lewises, he tends to do so through a focus on how he learned what he knows about them—who he interviewed, what archives he visited, and so on. The first few chapters describe at astonishing length the various kinds of evidence Woolaver has gathered to support his theory that Maud was born in 1901 and not, as usually assumed, two years later. There are similar lengthy discussions of whether or not she married Everett in a church, whether she knew the work of the American artist known as Grandma Moses, and so on. At times, also, whole chapters are filled with what appear to be fictional short stories Woolaver has written, sometimes about Maud and in what purports to be her point of view, sometimes about the places she lived in and his version of what it feels like to be there.

At one point, Woolaver reveals his own awareness of how annoying all these dissertations and digressions might be: “Oh My,” he says after a lengthy aside about a raft of eccentric and otherwise interesting characters he has known in Digby county,“If we effect a limit on biography, and bow before convention, not much of this has to do with Maud and Everett.” He then goes on to insist that it does, since the people he has described are somehow related to or otherwise connected to people with connections to the Lewises. By this logic he might as well have included me in the book, for I bet I know people whose cousins or uncles once dated the granddaughters of people who went to school with other people who lived down the highway from Maud and Everett. And forgive me for being conventional, but somehow, I retain the conviction that a biography should actually be about the people it purports to be about, not about friends of their friends and relations of their relations, and certainly not about the biographer’s own distant friends and relations.

Woolaver has clearly spend a lot of time and effort in putting together his body of knowledge of Maud and Everett Lewis. He has learned enough about them that he seems to have come to believe that he knows them intimately—so intimately that he’s entitled to reach very specific conclusions not just about what they did, but also, about who they are—what motivated them, sometimes even what they must have been thinking and feeling at certain moments in their lives. Maud and Everett Lewis may or may not have had the attitudes and motivations Woolaver is all too willing to provide for them, first as suppositions and then taken for granted as if they are incontrovertibly true. In his eyes, Maud emerges as something of a angel, and Everett an evil, self-seeking monster. I found both the overly angelic Maud and the overly malevolent Everett equally hard to believe in. Woolaver’s hostile and almost purely negative portrayal of Everett Lewis is particularly hard to accept.

It’s a pity that Woolaver felt so willing to invent reasons for Maud and Everett’s behaviour and then in later pages simply assume his inventions are the truth. It’s a pity that he has allowed himself to include everything he has felt like including, even poetic fictional scenes in which he imagines, for instance, what Maud is feeling and thinking as she has a conversation with a visiting moth. It's a pity that, having chosen to publish the book himself, he didn’t consider also hiring an editor less forgiving than himself—one who would have suggested massive cuts and who would have pointed out that the author Woolaver wants to refer to is Virginia Woolf, not Wolfe, or that the interview of one of Maud’s supportors he refers to is in a different documentary film than the one he names, or that it’s not safe for him to assume that readers will have read the same books as he has and thus immediately be able to make sense of cryptic references to Woolf or W.H. Auden or Graham Greene.

It's a pity especially because Woolaver has in fact, gathered an impressive amount of material on Maud Lewis, her work, her house, and her life in general--public records, school records, reminiscences from people who knew her, and much more. Learning about someone so far from the public eye for so much of her life and therefore, so unrecorded, is not easy. Among other things, Woolaver offers a convincing argument that the illness Maud suffered from in childhood and beyond was juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and provides evidence and makes a persuasive case for the existence of a daughter Maud had and put up for adoption while in her twenties; and his discussion of the ways in which the poor farm affected both Maud and Everett is revealing and instructive. At a quarter of the length and more rigorously centred on its subject, this could have been an excellent book—the materials to make it one are all there, buried in and overwhelmed by a huge excess of far less relevant material. I’d recommend this book to anyone who wants to know as much as there is currently to be known about the life of Maud Lewis—but with a strong warning about everything else you’ll have to put up with in order to learn about the book’s actual subject, and an equally strong warning about accepting Woolaver’s one-sided interpretations of his central characters.

1

1

YA fiction for Adults

I can't now remember why I decided to read this book, but I suspect it was because it's a combination of regular prose and cartoon panels--a sort of quasi graphic novel, then, but with the cartoon elements interspersed with a lot of just plain prose. This is a kind of fictional storytelling I can't quite get my mind around: why tell parts on the story in words and images and the rest just in words? And is there a difference in the effect of the differently presented sections, then?

Anyway, in order to read this, I had to know more about Zits, the daily comic strip which these authors produce and which features the same cast of characters. So I read a collection of Zits strips: Triple Shot Double Pump No Whip Zits. I found it sometimes clever and often amusing, but incredibly repetitive: based on a very limited range of jokes and clichés about teenagers and repeating those same jokes and clichés forever. Maybe it's better when you just get one a day?

After reading the strip, I then read this novel, which more or less just repeats the same old jokes and clichés in the context of a somewhat longer story arc. But what became most apparent as I read the novel was how very much the target audience for all this is adults, not actual teens like the main character. That becomes apparent mainly because readers are again and again being asked to know more and better than this ingenuous self-involved teen, and to laugh at all the ways in which he represents typical cliched teenhood. Confirming all sorts of easy and obvious stereotypes about teens doesn't necessarily close the book to an audience of teens, but inviting a kind of laughter that basically implies that all teens are silly and impossible and aren't adults ever so much sane and wise? That's not likely to appeal to teen readers. I hope. I hope not because the attitude being expressed is a sort of complacency: Golly, aren't teens ever so silly inevitably and always, and so thoughtless, and so incapable of being anything else. There's a kind of love for all this inadequacy and irresponsibility mixed in with the feeling superior to it, a kind of supposed dismay about teenagers that translates into a sense that being a clueless teenager is way better than having the responsibilities and worries of adulthood. As if. Anyway, i found it all very annoying. Not recommended. Maybe I'm too young for it?

2

2

Ick

Pretentious pseudo-philosophical whimsy about how men who dress well can awaken dead souls, give people the time of day, and teach everyone how to dream their dreams. Over complex and yet somehow under-drawn illustrations, in which supposedly non-creepy characters have no irises or pupils. As a wise sage once said about a different (and better) book: constant weader fwowed up.

Elegance and Melodrama

I can't deny that I was disappointed by this book--but then I had very high expectations for it. It is, as I expected, an amazing display of comics technique--beautifully drawn, with masterful variations in the rhythm of the panels, the use of a page, etc., etc.: all the things that allow visual panels organized on a page to tell a story. And the pictures exude a kind of assured sophistication and elegance, so that the pages are usually a pleasure to look out both with reference to the story they're telling and also as just as something visually pleasing to look at, with an interesting variation on the pattern of repeating boxes on every page.

What didn't work for me was the story these pictures help tell--a weepy melodramatic tale that seems like something about of a nineteen-thrties movie starring somebody like Jimmy Stewart. A loveably boyish but failing artist makes a deal with Death (embodied as his own dead crusty but charming Lionel-Barrymorish great uncle) to be able to mould any material as he wishes in return for agreeing to die in 200 days. Almost as soon as he begins to mould granite and concrete and the sides of buildings into massive works of art (which unfortunately, in the pictures, look incredibly crass and ugly), he falls in love and discovers he has a reason to live in addition to his art. The focus throughout is on what people allow themselves to do, how they prevent themselves from fulfilling their dreams, etc., and so there's all sorts of mid-cult self-help advice about how to live and how to feel and how to love. None of this did all that much to persuade me of the humanity of the characters, who seem way too loveable (and too loved by their creator) and also, way too busy doing endless self-analysis, to offer much in the way of psychological or moral insight--at least not much to me. It just seems, to be honest, sort of self-indulgent and silly.

My major concern, though is the huge disconnect between the quality and tone of the illustrations and of the story. I can see how the cool tasteful elegance of the style works to temper the fraught quality of the people and the events of the story, but in the long run, it simply, for me, doesn't temper them enough--and perhaps, for that reason, seems wrong, somehow, too cool, too much arousing expectations of Henry James and then offering Ann Landers.

One thing I did enjoy: how the talent Death gives the sculptor turn him into a sort of comic-book superhero, singlehandedly turning skyscrapers into giant statues, and makes the book as a whole a kind of clever twist on conventional superhero stories of damaged people with secret strength-except in this case, the superpower is an ability to make art. That's a nice twist.

Colonialism and Too Many Feet

This is a version of some comments I made on a fascinating post about this novel that Debbie Reese put up on her blog American Indians in Children's Literature.

The True Meaning of Smekday tells about eleven-year-old Gratuity's experiences as two different groups of aliens invade the earth. Rex does some very clever things here in terms of paralleling the alien invasions with what happened between imperialist invaders and Indigenous people in North America and elsewhere. I think, though, that Rex's main interest throughout appears to be in exploring the humor of the situation, and while that means there’s often clever and funny satire that emerges from the colonialist parallels, that doesn’t happen consistently. Sometimes the novel is a colonial satire, and sometimes it isn’t.

For instance, it seems that the appearance and character of the alien Gorg has satiric implications: they have the uniformity, the self-centered self-importance, and the obsessive single-mindedness of totalitarian overlords, like Hitler or the British raj or the European settlers of North America. But there is no satiric implication that I can find in the fact that the other aliens, the Boov, have a sizeable number of feet. It’s just a joke, just something that defines them as alien.

Similarly, I think, what happens sometimes resonates in terms of the history of relationships between Indigenous North Americans and European colonists and sometimes it doesn’t. And sometimes, much worse, it resonates in what I see as negative ways that I suspect Rex wasn’t even aware of.

I think that happens, for instance, with the portrayal of Chief Shouting Bear, whose shouting about Native rights turns out to be a role he adopts to keep people from getting too close to him and his secrets. I like how the Chief slyly manipulates stereotypes of angrily politicized Native Americans in order to keep people from interfering in his life. He creates a safe space for himself by pretending to be something that confirms other people's negative stereotypes and makes those other people want to avoid him. But while the distance between the stereotype and the real, clever, kind man who hides behind it seems to imply the falsity of the stereotype, it also in an odd way also confirms the stereotype: the novel never suggests that there aren’t a lot of angry Native Americans who shout too loudly about their land and their rights, etc. Nor does it suggest that the anger is justified and even necessary, or that is anything but just silly and laughable. Indeed, the novel seems to be sending up the supposed silliness of politicized Native people who want to make others aware of their rights at the same time as it seems to be expressing concern about how powerful outsiders oppress people and deprive them if their rights. The novel is just too interested in making jokes and being funny to be consistent enough to be effective as satire. As a result, it undermines its own satire.

My main concern with the novel, though, is that while it makes significant points about how colonizers oppress others, points that seem modeled on the history of European settlers and Indigenous North Americans, it finally seems to want to dismiss the significance of that history and invite readers of all sorts to believe that the past is the past, what’s over is over, and that since we’re really all alike we should be forgetting our differences (and apparently the history behind those differences) and just treat each other as equals and get along. Gratuity, the protagonist who is telling what happened, implies that sort of tolerance message when she says, “The Boov weren’t anything special. They were just people. They were too smart and too stupid to be anythng else.” And the Chief agrees: “When you’re Indian, you have people telling you your whole life ‘bout the people who took your land. Can’t hate all of ‘em, or you'll spend your whole life shouting at everyone.”

The novel also undermines its colonialist satire by identifying a number of other forms of oppressions of weaker people by more powerful ones: women by men, children by adults, etc. Even Gratuity herself has to acknowledge at one point that maybe she’s too bossy and should stop oppressing others. As a result, the specific history and issues of Native Americans become just one example of a more general attack on mean bullies who take advantage of weaker people; and the solution to that particular situation as well as all other situations and relationships is just being nice to others and treating them all as equals.

To me, that reads like a massive copout, a way of avoiding the important political and historical issues that still control and limit far too many lives. And like, for instance, a lot of multicultural rhetoric, it works to erase the ongoing significance of the specific history of Indigenous peoples—what makes their situation different from those of all the other groups who now live together in countries like the US.

One final point: for someone who spends a lot of time attacking and making fun of imperialists blind to the equal humanity of people they see as different and inferior to themselves, Rex himself, quite unconsciously, I suspect, makes a hugely imperialistic mistake. He asserts that the Boov force all the inhabitants of Earth to move to Florida, and then, changing their minds, to Arizona. But he then says nothing about how the Earthlings from, say, Europe or Africa, are going to manage to get to Florida. And when Gratuity arrives in Arizona, there is no mention of people who speak Swahili or Chinese, no mention of there being disputes involving people from different countries or continents, no mention of orders given in any languages other than English and Spanish. In fact, Rex has simply assumed that the Earth = the USA. All the humans who are not American are simply erased. It’s only in one sentence towards the end that Rex hints that maybe the Boov had rounded up other people in other parts of the world in different detention areas closer to where they live--a weird thing to suddenly tell readers about when we’ve been asked all along to assume that all humanity had ended up in Arizona. This is unconscious American imperialism at its finest, and as a Canadian, I found it exceedingly annoying.

All things considered: I think that The True Meaning of Smekday is often a very funny novel, and often a cleverly satiric one. But while it certainly has the potential to give readers of all ages a lot to think about, I find myself saddened by the ways in which it sets up parallels that allow for shrewd commentary on American Indian history and politics and then squanders the opportunity to pursue that commentary in favor of jokes and a kind of obvious and dangerous message of thoughtless universal equivalence and tolerance.

The Capital M Meaning of Capital L Life

I really enjoyed this novel until almost the end. It has a Dickensian thing going on: lots of detail, lots of eccentric characters; and even though it takes forever to describe all the details of almost everything, it's a pleasantly immersive experience. And for all the discussions of art and the sad emotions of the protagonists trying to come to terms with the disappointments and confusions of his life and the interesting questions about various kinds of fakery, there's also a surprisingly melodramatic thriller plot going on, and gangsters, and bloody acts of murder--an entertaining combination of introspection and violence. But then, horrifyingly, right at the end, the main character goes into about ten pages of confident speculation about the meaning of life, the universe, and everything. Tartt might well have felt that, after having spent so long writing so many many pages, she deserved an opportunity to tell us all what we we should be thinking about our lives and the world we live in. But somehow, this final sermon or advice column or post-Victorian pep talk ends up making the entire novel seem like just an excuse for the pontificating--an act of self-indulgence on the part of the novelist that dissipated my interest in everything that went before. I'm not going to go into what Tartt thinks the meaning of life is, because honestly, as soon as I realized what was going on and how the novel had turned into a how-to-be-human tract, I just stopped paying attention to anything but my horror at the blatancy of it all. Conclusion: a really good novel suddenly turning into a pretty bad one. If I were to give advice to other readers, i might say: read up to about page 760 or so--and then resist the impulse to continue onwards. That way, you'll have read a better novel than the one I read.

A Veterinary Approach to the Teenage Years

Bainbridge, David. Teenagers: A Natural History. Greystone. Vancouver: D & M, 2009.

(This is a reposting of a blog entry I originally posted some years ago (Here). I just came upon it again this week and decided it was worth another look.)

This is an incredibly bone-headed book, and I’m wanting to take a closer look at why because it seems to represent a specific kind of boneheadedness increasingly widespread now–a mechanistic conviction that whatever people do is substantially mandated by biology or some other sort of “natural” imperative imbed in us by evolution or anatomy and inescapable. In this case, what teenagers are (always are, it seems, and always must be) was established by the evolutionary development that produced homo sapiens–and while Bainbridge does acknowledge here and there the possibility that human beings might occasionally be influenced by their personal genetic makeup or history or the culture that surrounds them, he nevertheless falls back immediately into his basic, fundamental assumption: whatever teenagers do now, as a stereotyped group, must be what they have always done in some form or another throughout history and in every culture, because evolution made them that way and required that they act that way. There is really never anything that people choose to do that wasn’t in fact a choice actually made by the inherent will of their species trying to be the fittest to survive.

Indeed, his faith in the evolutionary imperative is so complete that he tends even to assume that counterproductive things that people do–things like experimenting with addictive drugs and such that might well lead them into serious trouble–must have emerged from some aspect of human biology that was a positive force in allowing human beings to survive. He says, for instance, that “even the most unpleasant changes [in puberty] confer some benefit on us, or at least they did as some point in the past. When you start to view puberty as a product of evolution,much of what happens to teenagers begins to make sense” (42). He then has to admit that there’s no known evolutionary advantage in various typical patterns of body hair, or in things like teenage acne. And he never considers the possibility that things of this sort might be the kinds of evolutionary mistakes that could end up dooming homo sapiens to the dustheap of history, and therefore be evidence of lack of fitness to survive. Even though he insists that homo sapiens has existed for little more than an eye-blink in terms of evolutionary processes, he sees every single aspect of human biology as nothing but evidence of what has kept us going and therefore what is and always must be true about us and what will and always explain all of our social behaviour–until, I suppose, a species fitter for survival comes along.

His absolute conviction that every aspect of our biology and behaviour emerges from the evolutionary imperative is revealed most clearly in his ongoing habit of using language that ascribes will to biological organisms–their main if not only urge is an inherent will for their species to continue, and so, he keeps saying, they decide to adapt their biology in an effort to do so.

I’m not about to dispute Bainbridge’s obviously substantial knowledge of human biology and of recent developments in the sciences that study it. He does seem to know a lot, and he does present it in clear and interesting ways. Nevertheless, he does then tend to jump illogically from what is known about biology to the conclusion that it accounts for things such as the typical behaviour of teenagers, their typical rebelliousness, etc. It seem fair to asserts, as he does, that “evolution has given us our teenage years for a very good reason–in the long run they help us to succeed as individuals (that is what evolution does” (4). But having a period in which one makes the biological transition between childhood and full maturity dos not necessarily mean what Bainbridge unquestioningly understands the teen age to be: a collection of cultural norms and stereotypes garnered from the popular culture of the last fifty or sixty years. He asserts, very unpersuasively, “We all know the teenage mind” (100), as if there was just one shared by all teenagers. Indeed, adults can share tales of their lazy, rebellious teenagers because “this stereotyped nature of teenage behaviour suggests that there are certain ordered, consistent changes that take place in all teenage minds” (113-114).

For Bainbridge, indeed, “teenagers are not a social idea–they are quite simply different from everybody else” (12). In asserting that, he ignores a vast history in which those in the teenaged years behaved quite differently that stereotypes imply they do now, and a huge spectrum of other understandings of how people do and/or ought to behave in their teenage years in the variety of differing cultures and subgroups existing even just now in the world today. In all these differing circumstances, I suppose, it might be possible that teenagers still felt and feel not only the same biological urges, but also, an urge towards the same culturally-mandated expressions of those urges, as do contemporary James Deans and Taylor Swifts and such, even though the culture they were or are part of didn’t acknowledge then as being distinctly teenage-like, as being evidence of a separate category of human existence in need of an name and an special kind of analysis and understanding. But I think it highly unlikely that young Buddhists in Asia or young serfs in medieval Europe or young Hutterites living apart from contemporary mainstream culture in colonies in Western Canada or young devout wives of Mormons patriarchs were or are all just secret Barbies and Jonas Brothers at heart.

For that matter, not even all the young, middle-class white people in first world English-speaking countries from which Bainbridge derives his stereotypes display the stereotyped behaviours that popular culture identifies as typically teenaged and that Bainbridge insists are biologically mandated. I can’t say that I much recognize the teenaged years of myself or my own three children in his descriptions of what it always is to be a teenager. His argument might be more convincing if he didn’t just take it for granted that what the media tells us teenagers are now is both true and universal and an inevitable product of biology. According to Bainbridge, all teenagers “undergo an active process of rejection of their parents which is probably essential for their development as individuals” (221). But surely a lot of teenagers in the past and now have made it and do still happily make it into adulthood without rejecting their parent’s values in any way at all. Does that mean they are biological mistakes and, presumably, therefore doomed not to reproduce enough to keep their genes surviving? It hardly seems likely.

For me, the most annoying aspect of Bainbridge’s work is that, in trying to establish that being teenaged is indeed a unique and special stage of human life, he had to invent both a childhood and an adulthood quite unlike it; and his version of childhood in particular is particularly unconvincing, not to mention, an insult to children.

He tends to assume that all adults everywhere always have been just like he is himself: “All adults have similar memories of adolescence, distorted, distanced, and rationalised by the lens of age” (76); furthermore, it happens not because of nostalgia or the imposition of cultural stereotypes on our own past, but because “our brain has changed since we were teenagers.” And in order to define teenagers as newly aware of and sensitive to relationships and the feelings of others, he seem to feel he has to insist that children are devoid of these qualities–that their biology prevents them from thinking deeply, or feeling deeply, or understanding anyone or anything deeply.

He says, “we now think we evolved children to be little brain incubators–charming, unthreatening people whose brains are not finished, but who do not eat much of our valuable food because they are small. It makes sense to keep them small for as long as possible, because all they have to do is talk all the time, break things, and manipulate adults” (69). I suspect Bainbridge is trying, and failing miserably, to be funny here.

Or again, the second decade of life is “a time when we start to ascribe extremely subtle and complex interpretations of the world around us–this is why a ten-year-old could not write a sonnet” (108). And yet some ten-year-olds do write sonnets, and many more have very complex understandings of the world and the people around them.

Or again, horrifically, “Children may be charming little people who can talk and think a little, but we do not become fully mentally human until we are teenagers” (132). Yes, I checked it–that’s an accurate quote.

Among other things, furthermore, as the teenae years begin, “many of us start to see ourselves as individuals at this time” (183). “As the first ten years of life elapse,” in fact, “children occasionally refer to how they see themselves and how they think others see them, but these flickerings of self-analysis are interspersed with long periods of an endearing ignorance of self. . . . While children are rather poor at self-analysis, preferring instead for adults to show them the correct way to do things, adolescents are the complete opposite” (189). Furthermore, “a major reason why depression often starts in adolescence is that this is the first time when the brain has sufficient cognitive abilities to be able to suffer it” (200). And we need to be teenagers in order to “start to discover the subtleties of nuance, sarcasm, irony, and satire” (138). Yeah sure–so much for Dr. Seuss and all.

All of that, of course, merely confirms some very old and very wrong assumptions about childhood–assumptions that have allowed and still do allow far too many adults to treat children cruelly or pre-emptorily, on the basis that they don’t have the feelings to be hurt by it or the intelligence to see through it.

In the light of the concerns I have with the arguments presented in this book, I probably shouldn’t be surprised to learn that Bainbridge is by profession a–wait for it–veterinary anatomist! Who better to understand and analyze the problems of human teenagers than an animal doctor, right? He says, “I must emphasize that, as a veterinary surgeon with zoological training, it is philosophically pleasing for me to view humans as ‘just another species.’ After all, they are animals like any other, subject to the same rules of biology as any other, and amenable to study” (15) In point of fact, they are not quite so amenable to study–Bainbridge complains more than once about the impossibility of conducting the appropriate experiments on human teenagers that would, for instance, allow scientists to determine the significance of chemicals essential in the developmental process by depriving control groups of them–shades of Dr. Mengele.

But the real problem here, once more, is that Bainbridge’s focus on humans as animals tends to ignore or slide over ethical issues–to conclude, for instance, that men are biologically mandated to be aggressive and women passive, so that controlling male aggression or women taking charge of their own fates come to be viewed as evolutionarily regressive acts, or perhaps, even, impossible. What am I make of a statement like this: “If men’s brains are hard-wired to be attracted to fine-limbed, smooth-skinned, high-voiced, round-faced people, does this explain paedophilia? Are male paedophiles simply men who are more attracted to the characteristics women retain from childhood than those women acquire to puberty” (61). If so, what ya gonna do about it, eh? Biology requires that these men prey on boys, so let ‘em at it.

In viewing humans as animals, Bainbridge also tends to ignore the ways in which we are cultural beings. “[I]t is obvious to any casual observer,” he insists, “that brains of teenage boys and teenage girls often work in different ways” (89)–their brains, mind you, not their culturally-inflected minds. In cartoons and bad movies and silly advice columns, yes–but in actual real life, as a matter of course? And note the taken-for-granted assumption that sex differences account for all gender differences: “surely a brain develops differently if it is housed in a male body than in a female body?” (90), and “Teenager inherit a brain that already knows what sex it is” (96–not surprisingly, Bainbridge has a hard time accounting for homosexuality, which he sees as both inherently genetic and counter-evolutionary, since it doesn’t lead to breeding). That’s really not all that far away from assuming that, say, brains are inherently different in bodies of different skin pigmentations. In fairness, I acknowledge that Bainbridge does wonder if “perhaps our sexuality is less hard-wired than a rat’s” (95).

In response to Bainbridge’s obsession with evolutionary explanations, I’m tempted to argue that the real reason for the success and survival of homo sapiens as a species has been its incredible imaginativeness and flexibility in developing differing kinds of social and cultural arrangements and understandings, and that rather than being at the mercy of its biology, it has survived and developed exactly because of its ingenuity in inventing a huge and complex and contradictory range of ways of organizing and understandings itself in response to that biology. That why there is history. The teen age has been significantly different in different times and places, in ways apparently not interesting to the veterinarian approach.

1

1

While a useful survey of all the different ways in which people have imagined the painter Tom Thomson in the almost a century since his death, this book is decidedly wacky--sometimes in a good way, sometimes not so much. The trouble is, Grace is most intent on showing how every description of a person's life is inherently fictional--which is true; but she then seems to assume that means that, as well as revealing the fictionality of the various biographies, documentary films, and so on that she describes, she is also free to invent her own Tom Thomson. She offers, for instance, a lengthy discussion, based very vaguely on a very few facts, of how Thomson might have actually been a gay man with a secret passion for one of his male friends. And all the while she is spending all those pages working out all the imaginary details of that supposed possibility, she keeps insisting that of course she's really just making it up, which basically made me wonder why she was telling it to me in such lengthy detail anyway. Weird. She also has a lot to say about how the Tom Thomson enshrined in legend is a celebration of a certain kind of female-avoiding masculinity as well as of a certain vision of Canada and the idea of the North, which, on the basis of the limited amount of evidence, isn't all that convincing.

A masterful example of using alternating narrative focalized through different characters who see each other quite differently than the ways in which they see themselves. That the characters each represent one of the cultural groups involved in a fraught moment of history makes their individual attitudes resonate in all sorts of intriguing directions. Centuries ago, a French missionary, a Haudenausonee captive, and the Wendat man who captures her to bring up as his daughter have a series of surprising encounters with, and understandings of, each other. The cultural values each of these characters takes for granted are both very believable and astonishingly alien to 21st century ideas about just about everything. I don't know how totally accurate any of this is, or indeed, how accurate it ever could be--but it certainly feels appropriately distant and yet, at the same time, very human.

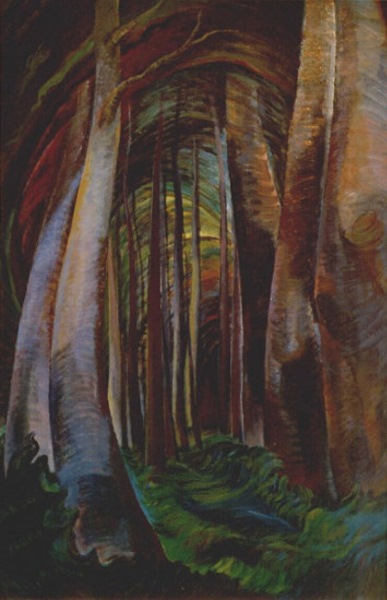

A good survey of the career of Emily Carr, with a focus on the formal and structural qualities of her paintings. The text reveals a a series of important stages or periods and the kinds of things she focussed on in those times--especially a move from paintings that depict West Coast Aboriginal totems, etc., to a concern with the spiritual aspects of dark forest interiors. There are a lot of wonderful paintings in the many plates--indeed, they are so many plates that together they create a visual sense of how obsessively Carr worked on similar ideas, and how successfully she turned those ideas into energetic paintings.

.

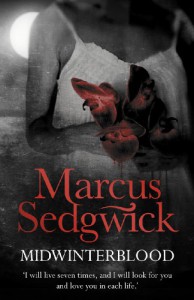

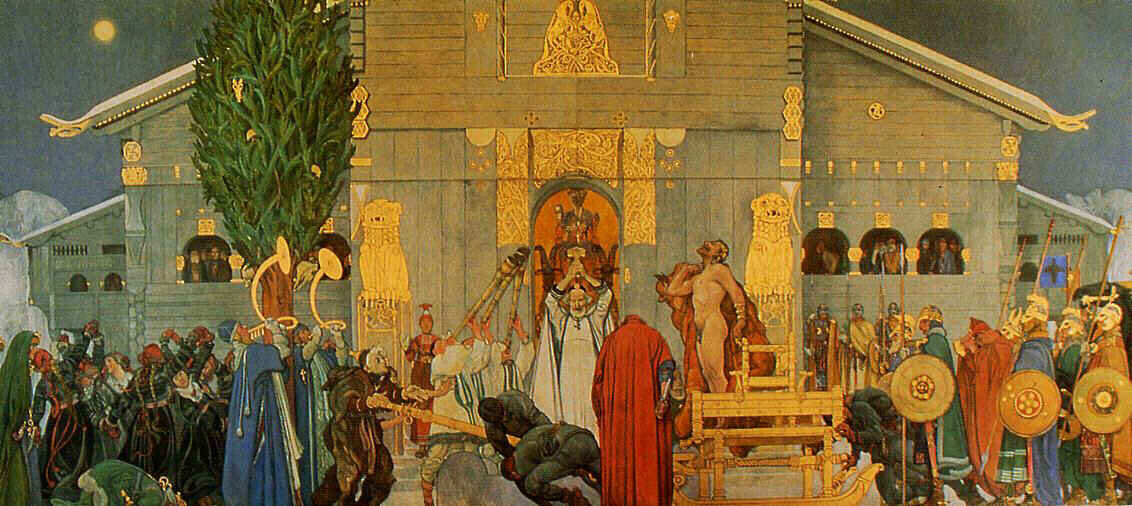

A set of interconnected short stories set in the same place in different times, from the distant past to the fairly near future. The connections relate to a pledge made in the past that manifests itself in a variety of different ways, for different (albeit similarly named) people across the centuries. It's a clever mystery then, and its movement backward from the future down into ever earlier pasts offers tantalizingly similar details and hints of what might be connections, until a last section that returns to the time of the first one ties them all together. It's all related to a large painting made in 1915 by the Swedish painter Carl Larsson for the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm but not hung there until many decades later. The painting depicts an episode in a myth about an ancient king who offers himself as a sacrifice in order to bring an end to a famine afflicting his subjects--one of the stories tells of a similar painter and pairing with a slightly different name.

As well as being a pretty terrific artist, Emily Carr was a landlady for a couple of decades--and just about as eccentric as many of her tenants were. This book describes everyone's eccentricities, including her own, with a refreshing degree of snippishness and an honesty about her tenants' failings and her own--although I have to admit that she seems somewhat less conscious of her own than those of the tenants. An enjoyable book, although less revealing of Carr as an artist than, say, her biography Growing Pains.

A detailed report of the childhood experiences, and fantasies, and dreams, of David B., centred around his older brother's epilepsy and the ways in which it drove his family into an astonishing range of weird cults and cures. It's all kind of unsettling, albeit in a fascinating way. David B. gives equal space to what actually happened and what kind of fantasies he surrounded it with, in his mind and on paper. The drawings are dark and brooding and very elegant--a beautiful vision of some ugly things happening.